As a new year gets underway, I’ve seen a lot of people choosing their one word for 2020. The purpose is to give each of us an inspirational lens to focus on in our personal and/or work lives in the year ahead. For example, a colleague of mine chose the word JOY, and everyday since then she’s been tweeting out something that brought her joy that day. She’s using this small act to help her re-frame how she views her life on a daily basis.

I’d like to offer up a twist on this challenge. If you’ve already chosen a word for 2020, that’s okay! You can do this challenge, too, because my challenge is about removing a word for 2020, two words actually. In the year ahead, I challenge educators across all grades and positions to remove the words high and low from their vocabulary for describing children.

As Annie Forest shares in her thoughtful blog post on this topic, “… I really believe that our words matter. Words have power. As teachers, we need to be careful of the words we say.”

I used to not be as careful about the words I used. Let me be vulnerable and tell you about a few of my own students from over the years who I, not knowing any better at the time, labeled as high kids or low kids. (Note: I’m using pseudonyms for each of the students.)

Rachel was one of my low kids. She had an extremely difficult time with single- and multi-digit computation. We worked together on modeling different strategies, but Rachel didn’t seem to retain what she was learning and consistently made mistakes. One day we played a game with cards showing different combinations of coins. The goal of the game was to look at an array of 12 cards and find pairs that total a dollar. For someone who struggled with computation, I expected this game to be a challenge for Rachel. I pulled up beside her, ready to provide assistance. Imagine my surprise when she found a match almost immediately…and then found another…and another. She was the master at this game! There was something about finding totals with money that cut through all the red tape that was bogging her down with bare naked computation problems.

Lily was one of my high kids. Answers came easily to her, especially if they involved using learned procedures. What didn’t come easily to her was justifying her thinking. Whenever I questioned her answers or probed for more explanation, she struggled and second-guessed herself. She was also very quiet and didn’t seem comfortable sharing her thinking during group discussions. Lily appeared to have a lot of anxiety around being correct and being seen as competent by the teacher and her peers.

Hector was one of my low kids. He struggled with multi-digit computation and word problems. He worked slowly, made errors, and generally seemed disinterested in the work we were doing. As we kicked off a new fraction unit, we explored different ways to divide geoboards into halves and fourths. Hector lit up! He found so many different ways to show the fractions, and he was able to prove his answers.

Fast forward to later in the unit where students had to locate numbers on a number line. Hector came up to me and said, “I think 5/8 comes after 3/5 on the number line.”

I asked, “How do you know?”

Hector thought for a moment and then responded, “Because 3/5 is equal to 6/10 and 6/10 is 1/10 away from 5/10 which is a half. And 5/8 is 1/8 away from 4/8 which is also a half. 1/8 is bigger than 1/10 so it’s further away from a half, so 5/8 is after 3/5 on the number line.”

I’ll be perfectly honest, I did not follow his explanation at all the first time he told it to me. After having him walk me through it one more time, I realized that he had used the fraction 1/2 as a benchmark in such a clever and useful way. Even better, he had figured it out all on his own.

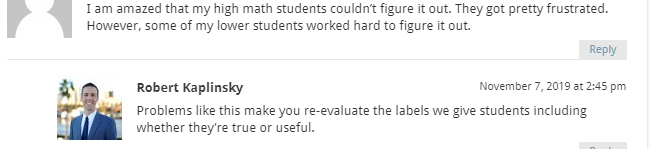

Reflecting on Rachel, Lily, and Hector, reminds me of this exchange Barbara Beske shared on Twitter:

Looking back, I know now that the labels I gave my students were neither true nor useful. To quote Rachel Lambert, an assistant professor at UC Santa Barbara:

“It’s incredibly difficult to accurately level students. Students and learning are much more complex than simple levels. It is a false premise that it’s easy to bucket children and that those buckets are meaningful.”

And while these labels might not be true or useful, I’ve learned they can definitely be harmful. The labels we give students influence our expectations for those students, even if we aren’t aware of it. To learn more about this, check out Andrew Gael’s exceptional ShadowCon talk from the 2018 NCTM Annual Meeting:

We also need to consider who we tend to label as being low and high students, especially considering how sticky these labels can be over many years of a student’s school career:

“For years, schools have relied on testing to sort students into groups or tracks, presumably for the purpose of efficiently meeting their learning needs. These practices have persisted despite evidence from research on tracking that has shown that such practices almost always result in separating students by race and SES. When this occurs, invariably low-income and minority students are consistently more likely to be placed in slow and remedial groups, while the most affluent and privileged children are generally placed in advanced groups (Oakes, 2005).”

Excellence Through Equity: Five Principles of Courageous Leadership to Guide Achievement for Every Student

To go back to Annie Forest’s quote from the beginning of this post, “… I really believe that our words matter. Words have power. As teachers, we need to be careful of the words we say.”

So in the year ahead, I challenge you to remove the two words low and high from your vocabulary when talking about students.

Instead, let’s speak of students in ways that see them as whole people and maintain their dignity and humanity. (h/t Nicole Bridge and Heidi Fessenden) Annie closed her post with suggestions of language we can try using. I’ve made a few modifications based on language I’ve heard over the years.

| Instead of… | Try… |

| My high fliers need a challenge. | The students who have mastered this concept need additional challenge. |

| My low babies won’t be successful with this lesson. | There are some students who will need additional supports in order to be successful with this lesson. |

| My group is really low this year. | What I’ve done in the past isn’t working as well this year. |

| The shy kids don’t like to participate during number talks. | There are some students that aren’t as comfortable sharing with the group. |

| The ELs can’t read the directions on their own. | The directions may be difficult for some of my students to read on their own. |

UPDATE 1 – Robert Kaplinsky (quoted earlier in the post) shared a tweet from Marian Dingle that prompted him to take more action around this issue. If you have some time, I highly recommend reading through the conversation Marian’s tweet kicked off back in November:

UPDATE 2 – Rachel Lambert (quoted earlier in this post) recently gave an inspiring 5-minute talk smashing the myth of low kids and high kids. Check it out!

Thank you for your writing!!!! This speaks to my heart in such a tangible way.

I would add one word to your rreplacement phrases: yet.

Thank you!

LikeLike

Love This!!

LikeLike

Thank you for writing! I agree that labeling students does define your expectations of them.

LikeLike